Linear perspective in painting. Main secrets

Contents:

The vast majority of paintings and frescoes over the past 500 years have been created according to the rules of linear perspective. It is she who helps to turn 2D space into a 3D image. This is the main technique by which artists create the illusion of depth. But far from always, the masters followed all the rules of perspective construction.

Let's take a look at a few masterpieces and see how artists built space through linear perspective at different times. And why did they sometimes break some of her rules.

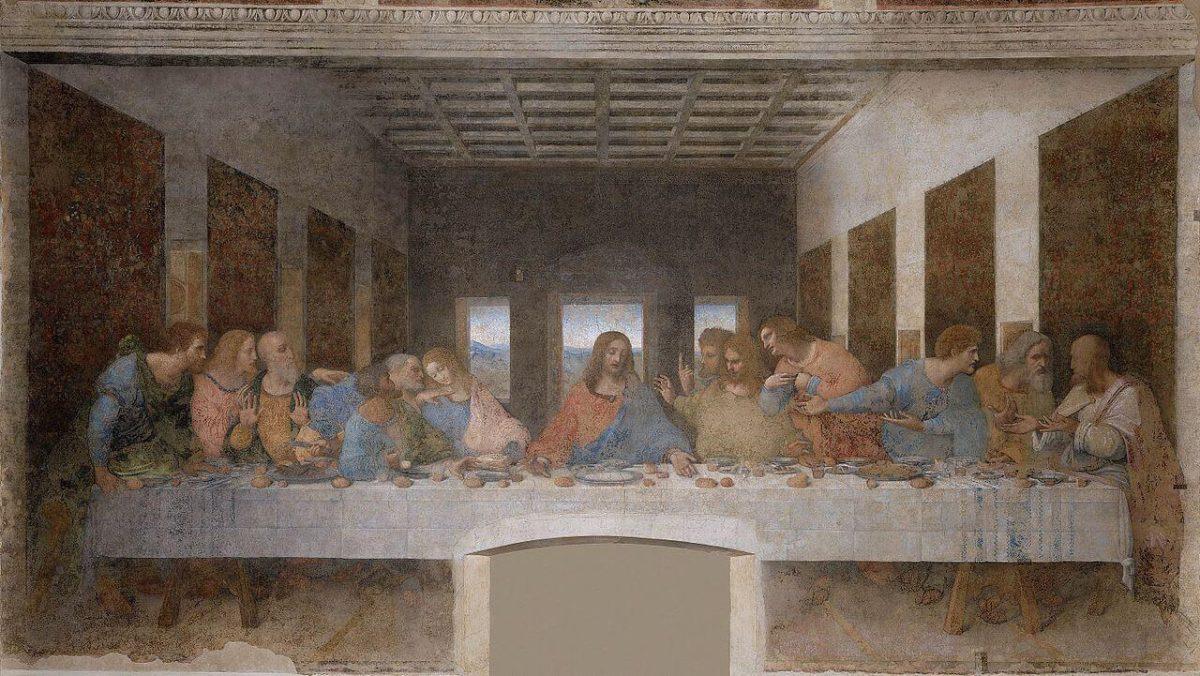

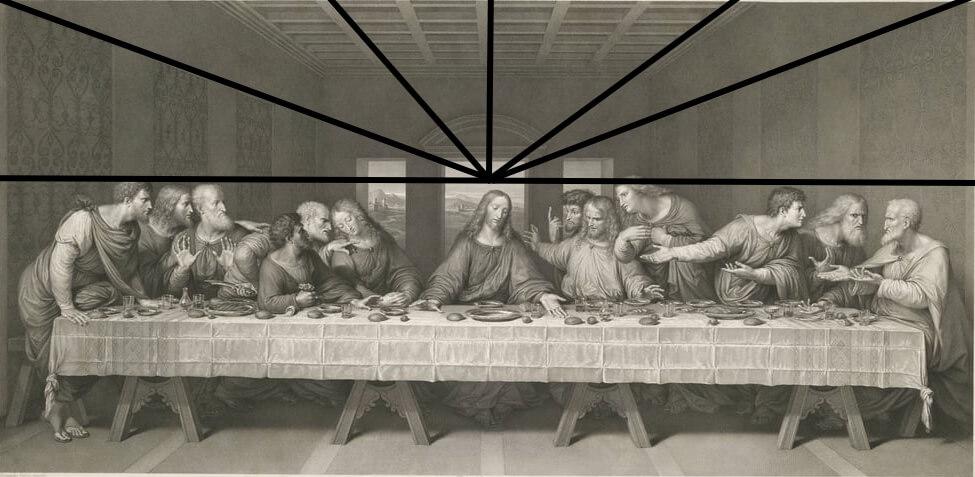

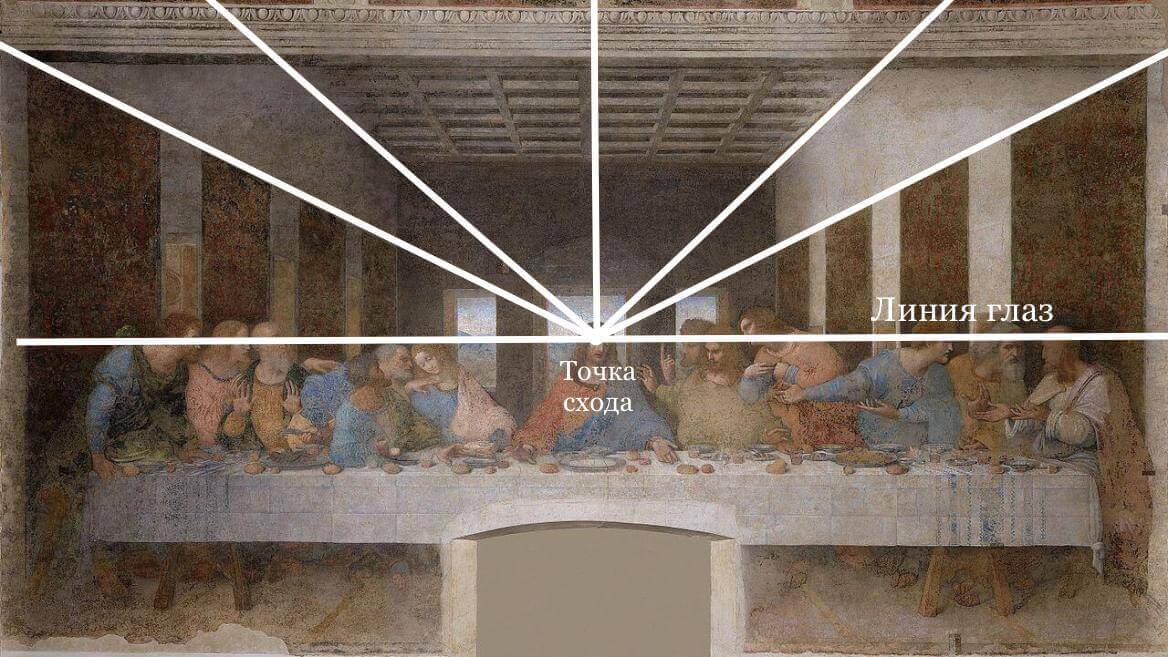

Leonardo da Vinci. The Last Supper

During the Renaissance, the principles of direct linear perspective were developed. If before that artists built space intuitively, by eye, then in the XNUMXth century they learned how to build it mathematically accurately.

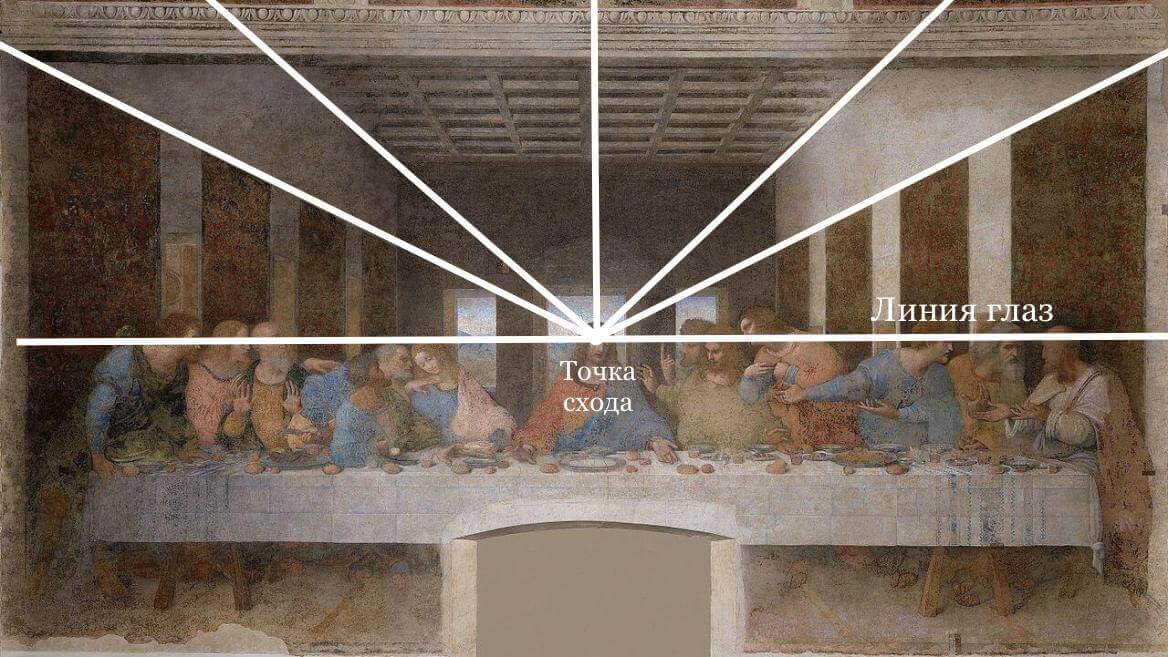

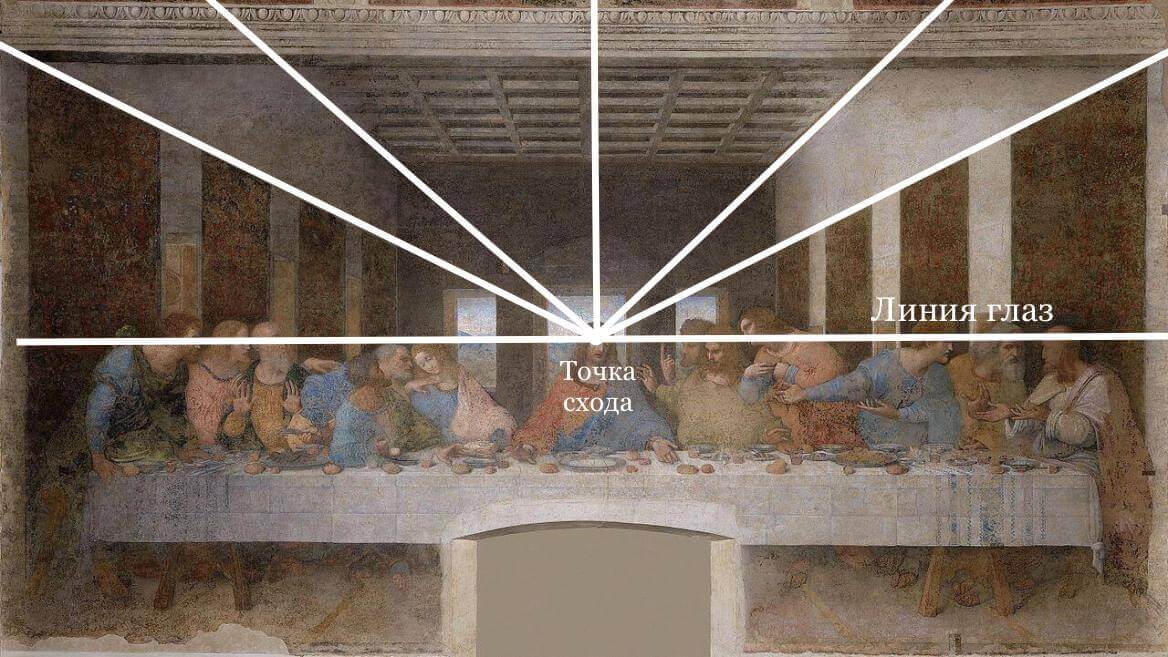

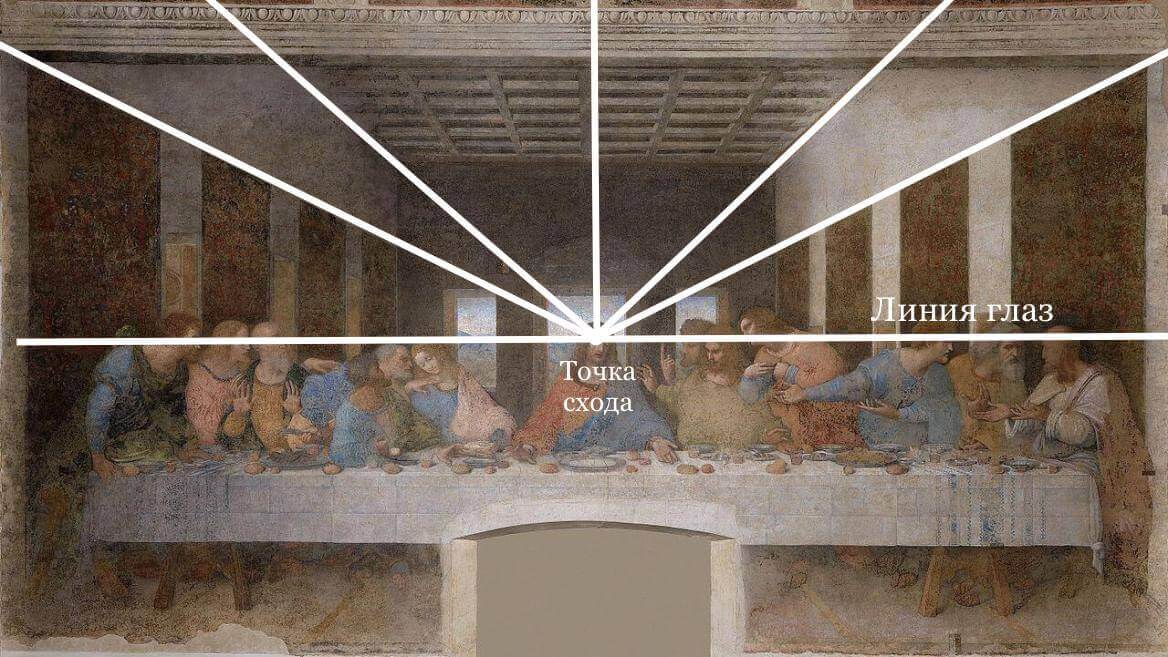

Leonardo da Vinci at the end of the XNUMXth century already knew perfectly well how to build space on a plane. On his fresco "The Last Supper" we see this. Perspective lines are easy to draw along the lines of the ceiling and curtains. They connect at one vanishing point. Through the same point passes the horizon line, or the line of the eyes.

When the real horizon is depicted in the picture, the line of the eyes just passes at the junction of heaven and earth. At the same time, it is most often in the area of \uXNUMXb\uXNUMXbthe faces of the characters. All this we observe in Leonardo's fresco.

The vanishing point is in the area of the face of Christ. And the line of the horizon passes through his eyes, as well as through the eyes of some of the apostles.

This is a textbook construction of space, built according to the rules of DIRECT linear perspective.

And this space is centered. The horizon line and the vertical line passing through the vanishing point divide the space into 4 equal parts! This construction reflected the worldview of that era with a strong desire for harmony and balance.

Subsequently, such a construction will occur less and less. For artists, this will seem too simple a solution. They bblow and shift the vertical line with the vanishing point. And raise or lower the horizon.

Even if we take a copy of the work of Raphael Morgen, created at the turn of the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries, we will see that he could not ... withstand such centricity and shifted the horizon line higher!

But at that time, building a space like Leonardo's was an incredible breakthrough in painting. When everything is verified accurately and perfectly.

So let's see how space was depicted before Leonardo. And why his "Last Supper" seemed something special.

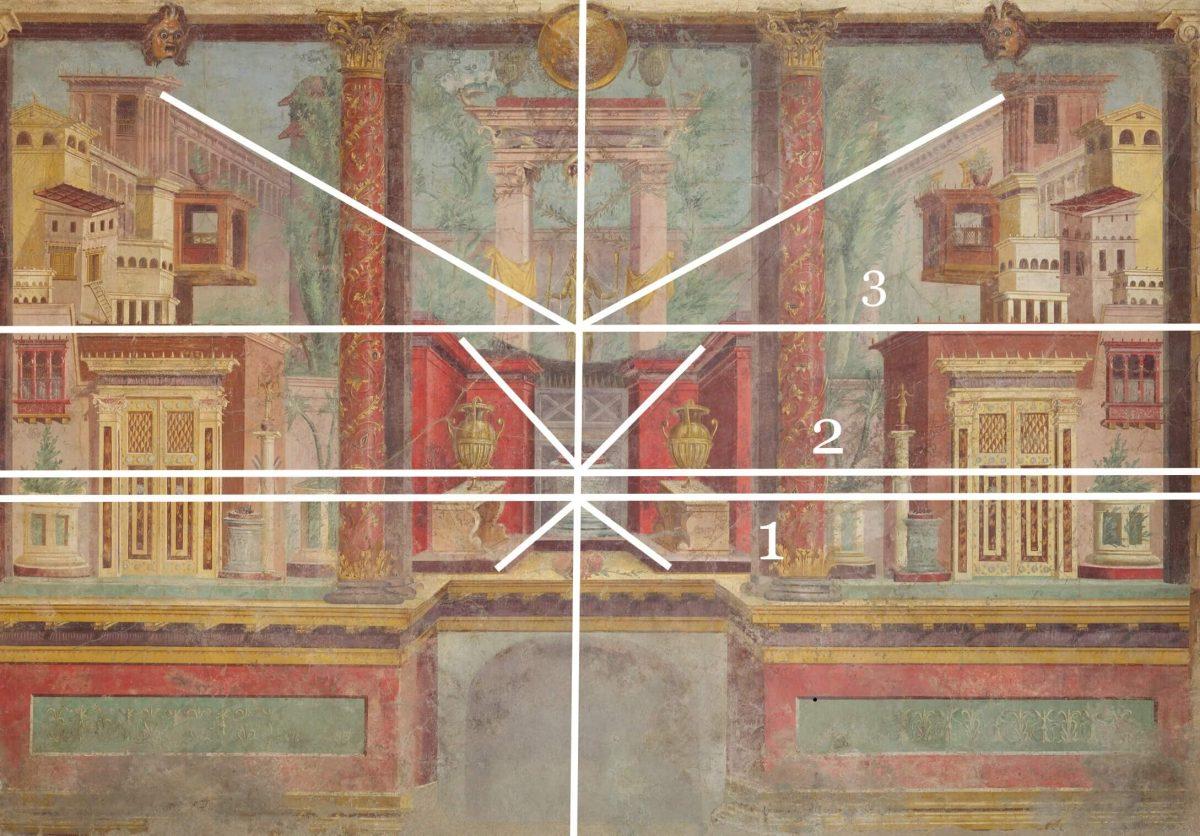

antique fresco

Ancient artists depicted space intuitively, using the so-called observational perspective. That is why we see obvious errors. If we draw perspective lines along facades and surfaces, we will find as many as three vanishing points and three horizon lines.

Ideally, all lines should converge at one point, which is located on the same horizon line. But since the space was built intuitively, without knowing the mathematical basis, it turned out just like that.

But you can not say that it hurts the eye. The fact is that all vanishing points are on the same vertical line. The image is symmetrical, and the elements are almost the same on both sides of the vertical. This is what makes a fresco balanced and aesthetically beautiful.

In fact, such an image of space is closer to natural perception. After all, it is difficult to imagine that a person can look at the cityscape from one point, standing still. Only in this way can we see what mathematical linear perspective offers us.

After all, you can look at the same landscape either standing, or sitting, or from the balcony of the house. And then the horizon line is either lower or higher ... This is what we observe on an antique fresco.

But between the antique fresco and Leonardo's Last Supper there is a large layer of art. Iconography.

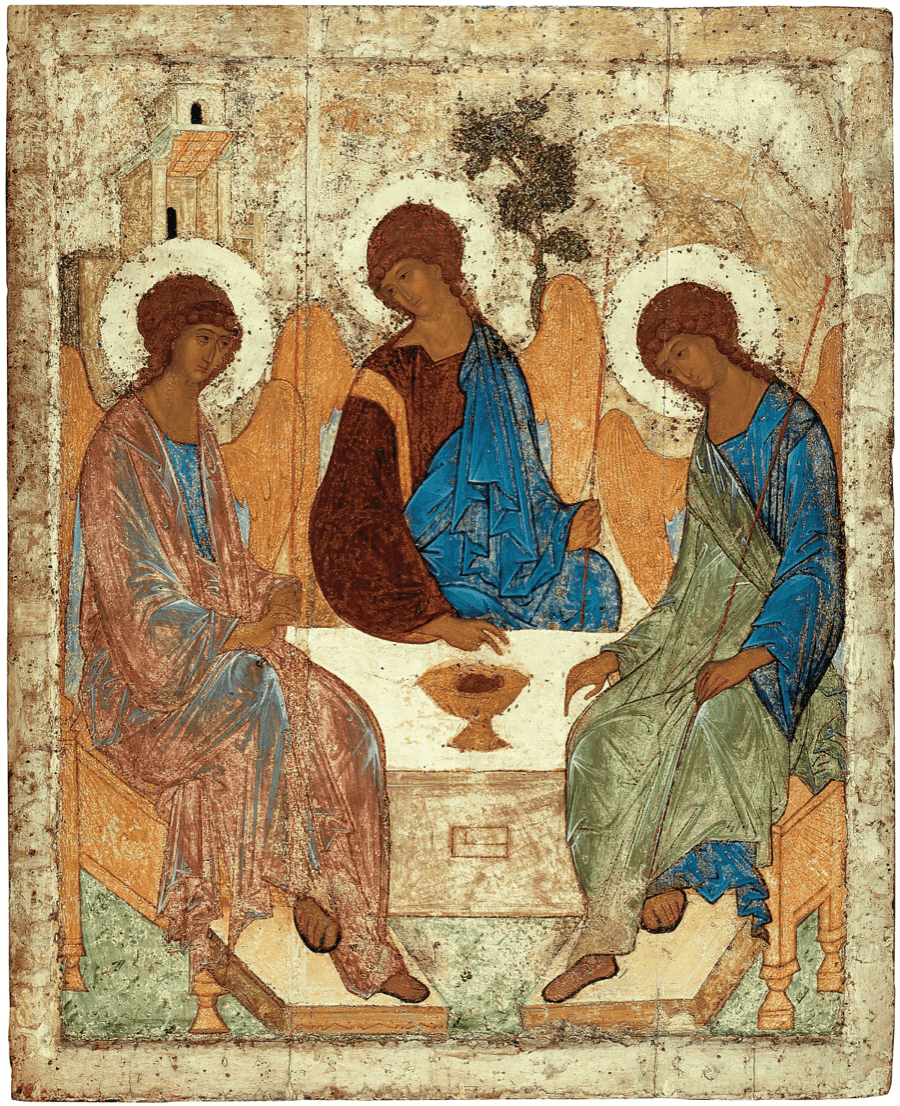

The space on the icons was depicted differently. I propose to take a look at Rublev's "Holy Trinity".

Andrei Rublev. The Holy Trinity.

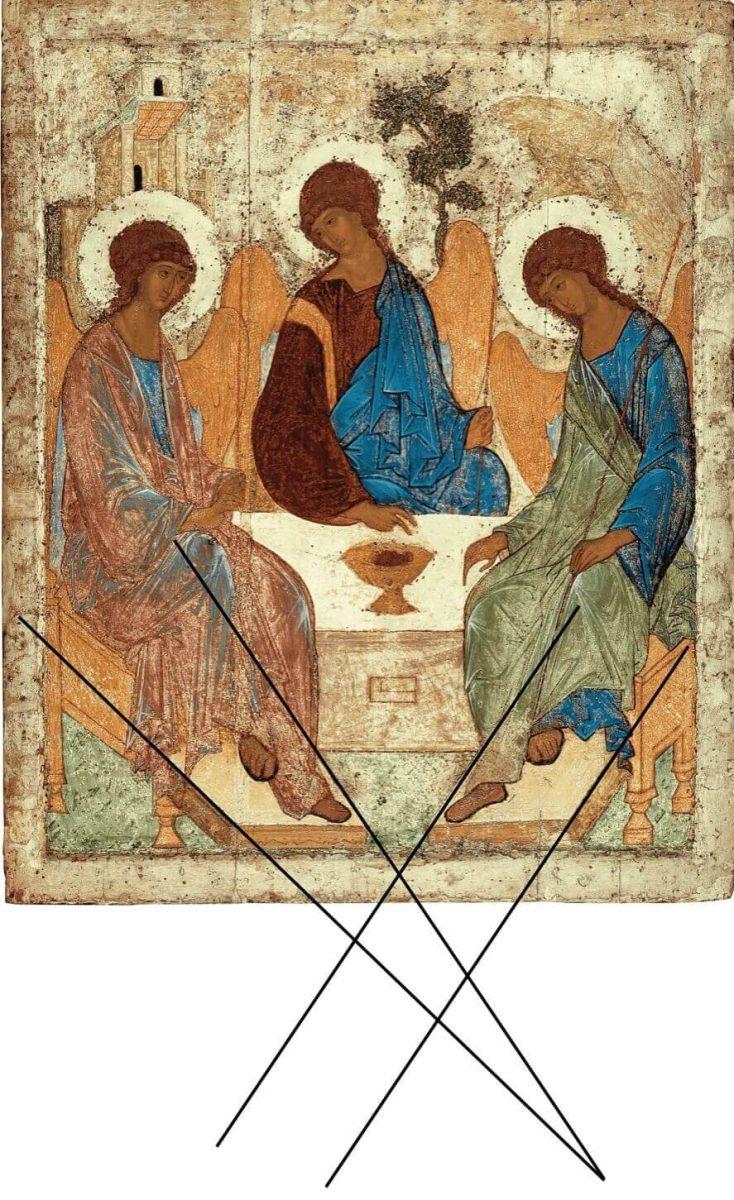

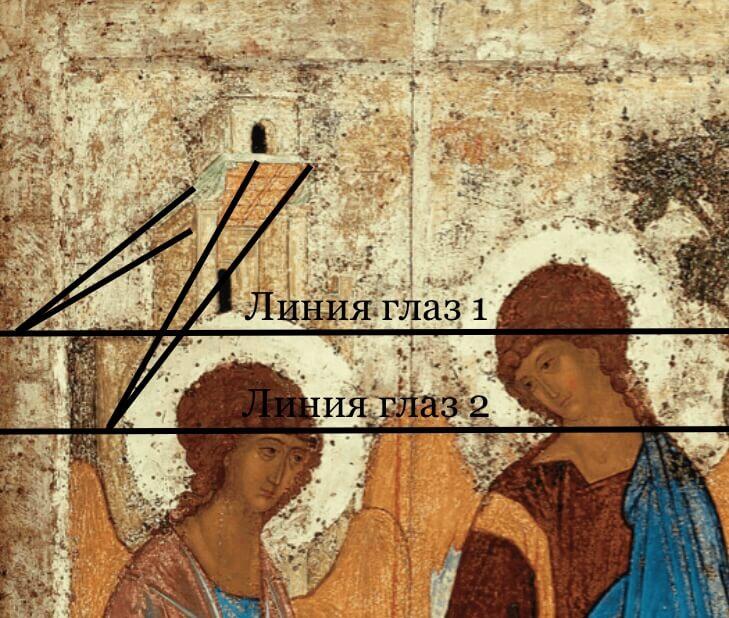

Looking at Rublev's icon "Holy Trinity", we immediately notice one feature. The objects in its foreground are clearly NOT drawn according to the rules of direct linear perspective.

If you draw perspective lines at the left footstool, they will connect far beyond the icon. This is the so-called REVERSE linear perspective. When the far side of the object is wider than the one closer to the viewer.

But the perspective lines of the stand on the right will never intersect: they are parallel to each other. This is an AXONOMETRIC linear perspective, when objects, especially not very elongated in depth, are depicted with sides parallel to each other.

Why did Rublev depict objects in this way?

Academician B. V. Raushenbakh in the 80s of the XX century studied the features of human vision and drew attention to one feature. When we stand very close to an object, we perceive it in a slight reverse perspective, or else we do not notice any perspective changes. This means that either the side of the object closest to us seems slightly smaller than the far one, or its sides are seen to be the same. This all applies to the observational perspective as well.

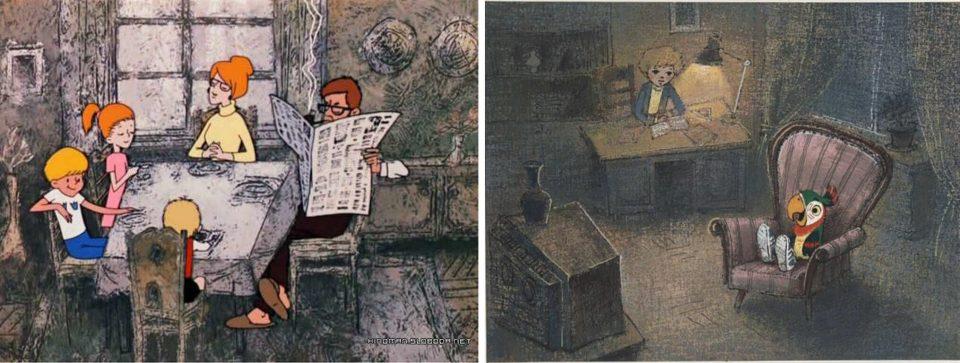

By the way, this is why children often draw objects in reverse perspective. And they also perceive cartoons with such a space easier! You see: objects from Soviet cartoons are depicted in this way.

Artists intuitively guessed about this feature of vision long before Rauschenbach's discovery.

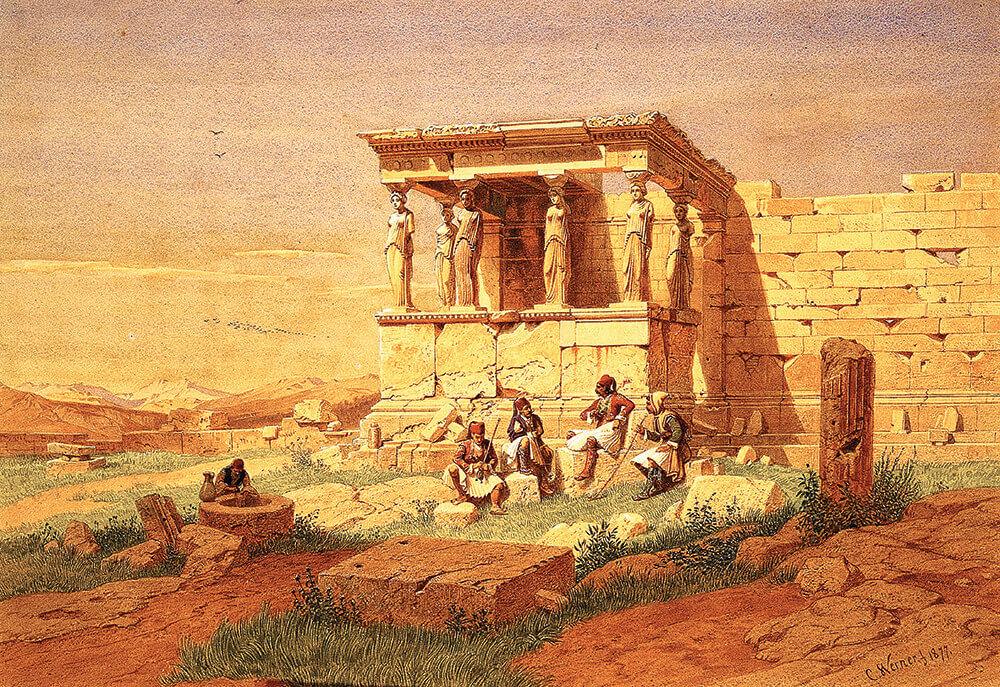

So, the master of the XIX century built the space, it would seem, according to all the rules of direct linear perspective. But pay attention to the stone in the foreground. It is depicted in a light reverse perspective!

The artist uses both direct and reverse perspectives in one work. And in general, Rublev does the same!

If the foreground of the icon is depicted within the framework of an observational perspective, then in the background of the icon the building is depicted according to the rules of ... direct perspective!

Like the ancient master, Rublev worked intuitively. Therefore, there are two lines of eyes. We look at the columns and the entrance to the portico from the same level (eye line 1). But on the ceiling part of the portico - from the other (eye line 2). But it's still a direct perspective.

Now fast forward to the 100th century. By this point, linear perspective had been very well studied: more than XNUMX years had passed since the time of Leonardo. Let's see how it was used by the artists of that era.

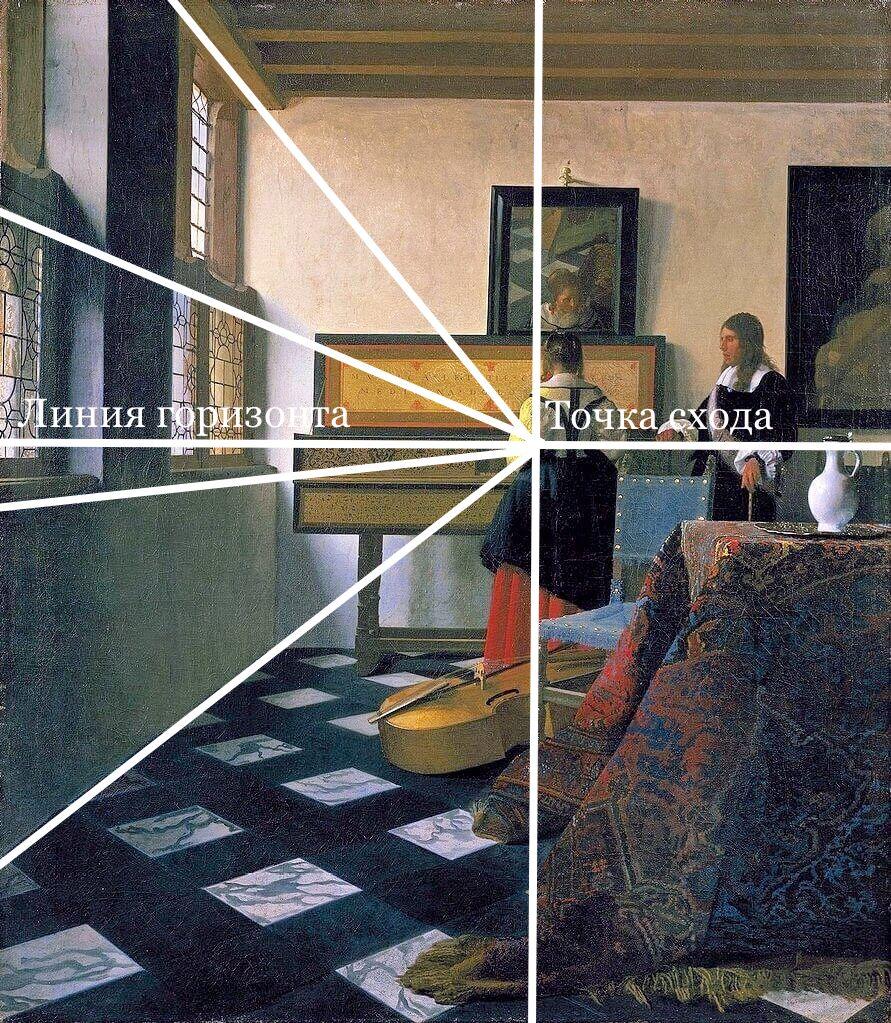

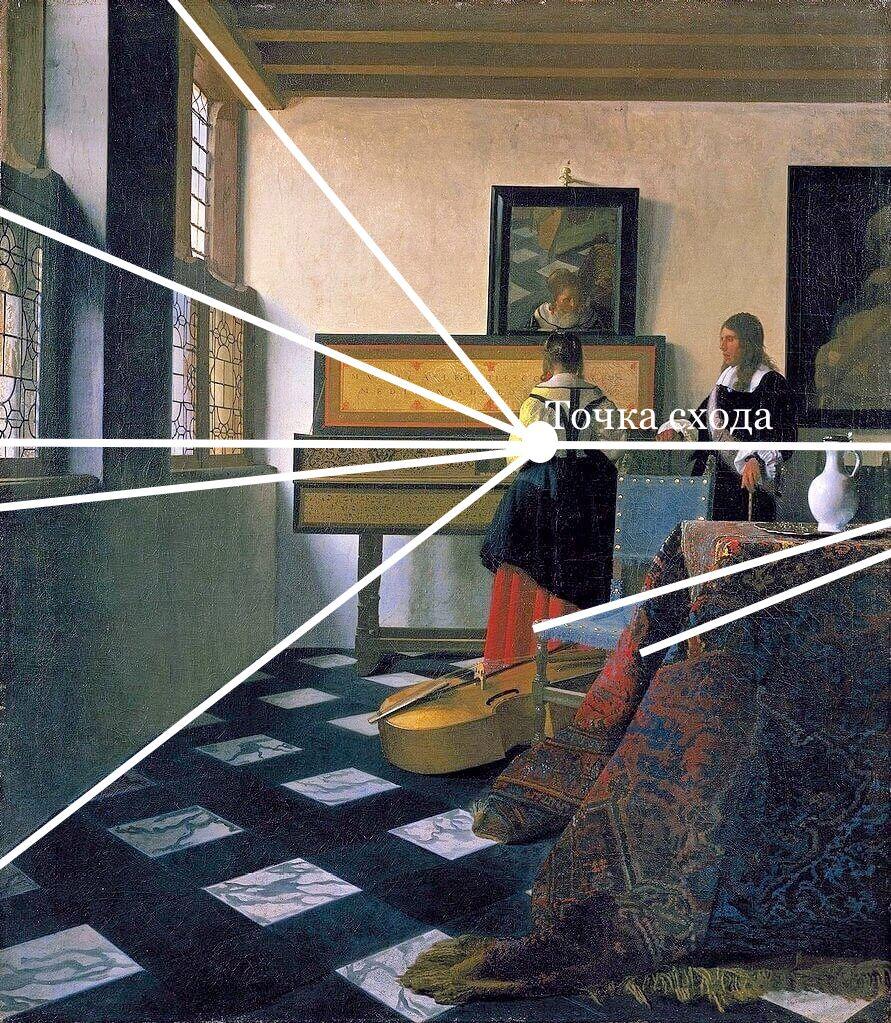

Jan Vermeer. Music lesson

It is clear that the artists of the XNUMXth century already masterfully mastered linear perspective.

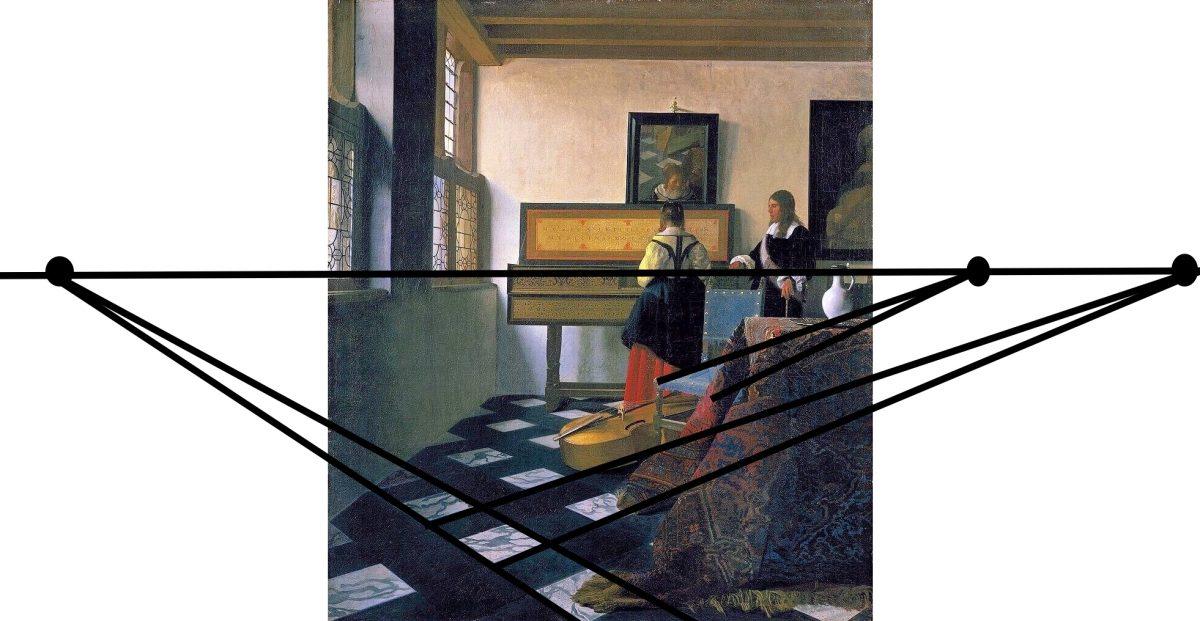

See how the right side of the painting by Jan Vermeer (to the right of the vertical axis) is smaller than the left?

If in Leonardo's Last Supper the vertical line is exactly in the middle, then in Vermeer it already shifts to the right. Therefore, the perspective of Leonardo can be called CENTRAL, and Vermeer - SIDE.

Due to this difference, in Vermeer we see two walls of the room, in Leonardo - three.

In fact, since the XNUMXth century, premises have often been depicted in this way, with the help of a LATERAL linear perspective. Therefore, rooms or halls look more realistic. Leonardo's centrality is much rarer.

But this is not the only difference between the perspectives of Leonardo and Vermeer.

In The Last Supper, we look directly at the table. There are no other pieces of furniture in the room. And if there was a chair on the side, thrown at an angle to us? Indeed, in this case, the promising lines would go somewhere beyond the fresco ...

Yes, in any room, everything, as a rule, is more complicated than Leonardo's. Therefore, there is also an ANGULAR perspective.

Leonardo has it purely FRONTAL. Its sign is just one vanishing point, located within the picture. All perspective lines meet in it.

But in Vermeer's room we see a standing chair. And if you draw promising lines along his seat, they will connect somewhere outside the canvas!

And now pay attention to the floor at Vermeer's work!

If you draw lines along the sides of the squares, then the lines will converge ... also outside the picture. These lines will have their own vanishing points. But! Each of the lines will be on the same horizon line.

Thus, Vermeer connects the frontal perspective with the angular one. And the chair is also shown with the help of an angular perspective. And its perspective lines converge at a vanishing point on a single horizon line. How mathematically beautiful!

In general, using the horizon line and vanishing points, it is very easy to draw any floor in a cage. This is the so-called perspective grid. It always turns out very realistic and spectacular.

And it is from this floor that it is always easy to understand that the picture was painted before the time of Leonardo. Because without knowing how to build a perspective grid, the floor always seems to move somewhere. In general, not very realistic.

Now let's move on to the next, the XNUMXth century.

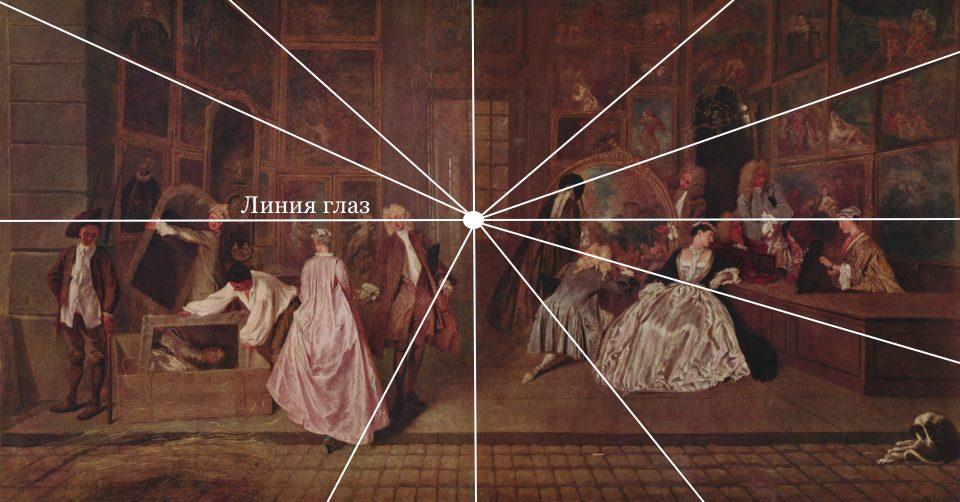

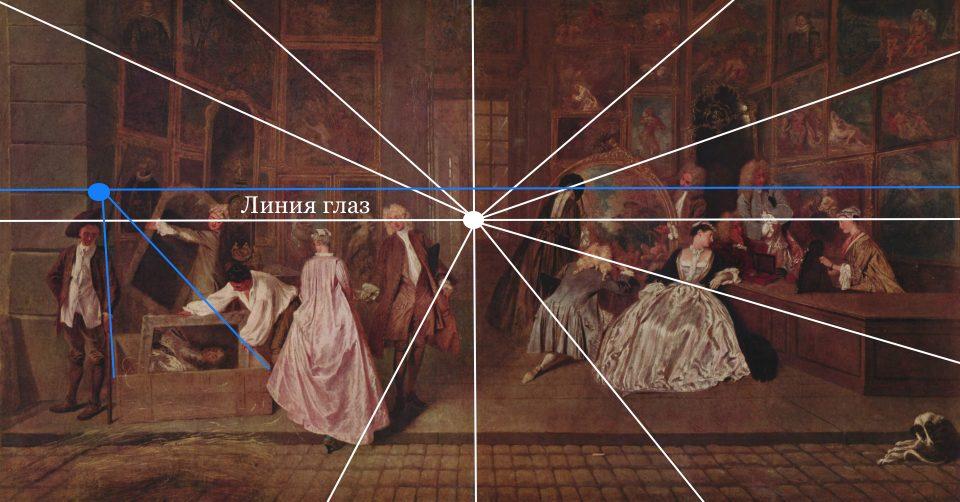

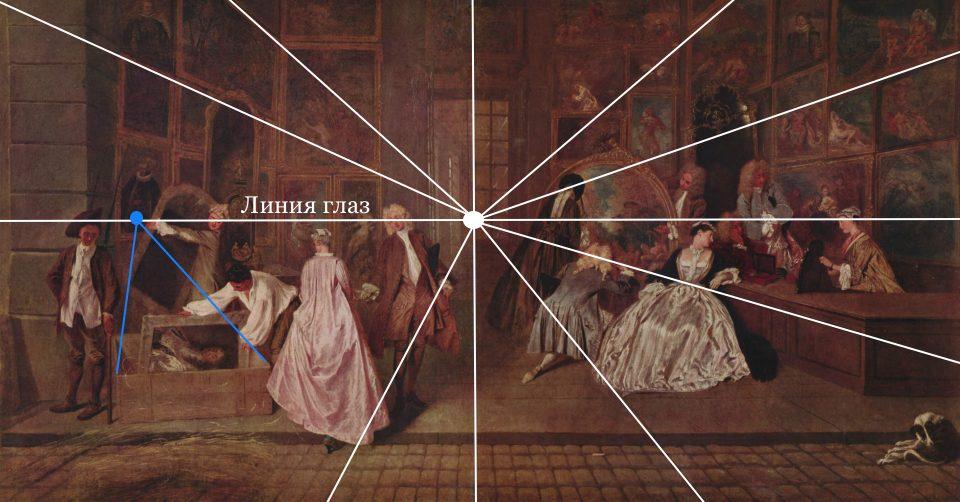

Jean Antoine Watteau. Signboard of Gersin's shop.

In the XNUMXth century, linear perspective was mastered to perfection. This is clearly seen in the example of Watteau's work.

Perfectly designed space. Such a pleasure to work with. All perspective lines connect at one vanishing point.

But there is one very interesting detail in the picture ...

Pay attention to the box in the left corner. In it, a gallery worker puts a picture for the buyer.

If you draw perspective lines along its two sides, then they will connect on ... a different line of eyes!

Indeed, one side of it is at a sharp angle, and the other is almost perpendicular to the line of the eyes. If you saw this, then you will not be able to ignore this strangeness.

So why did the artist go to such an obvious violation of the laws of linear perspective?

Since the time of Leonardo, it has been known that linear perspective can significantly distort the image of objects in the foreground (where perspective lines go to the vanishing point at a particularly sharp angle).

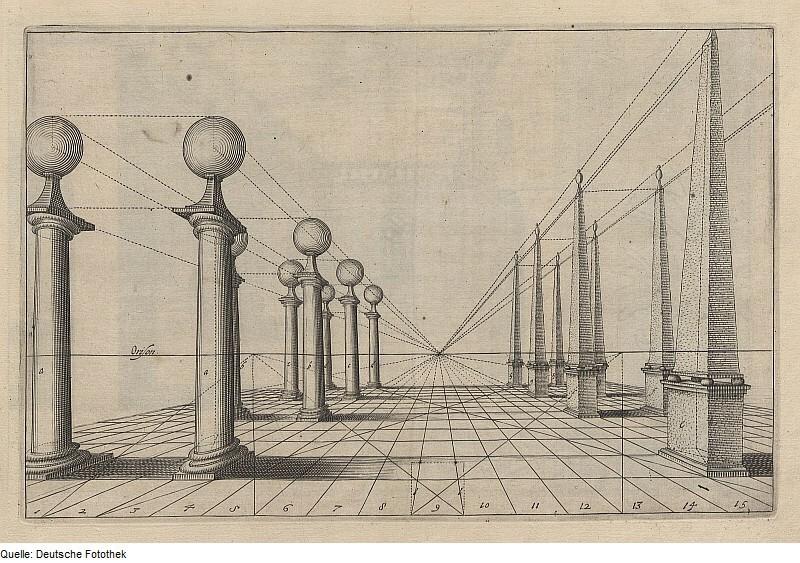

This is easy to see in this XNUMXth-century drawing.

The bases of the columns on the right are square (with equal sides). But due to the strong slope of the lines of the perspective grid, the illusion is created that they are rectangular! For the same reason, the columns, round in diameter, on the left appear ellipsoidal.

In theory, the round tops of the columns on the left should also be distorted and turn into ellipsoids. But the artist depicted them as round, using an observational perspective.

Likewise, Watteau went on a violation of the rules. If he had done everything right, then the box would have turned out to be too narrow at the back.

Thus, the artists returned to the observational perspective and focused on how the subject would look more organic. And deliberately went to some violations of the rules.

Now let's move to the XNUMXth century. And this time let's see how the Russian artist Ilya Repin combined linear and observational perspectives.

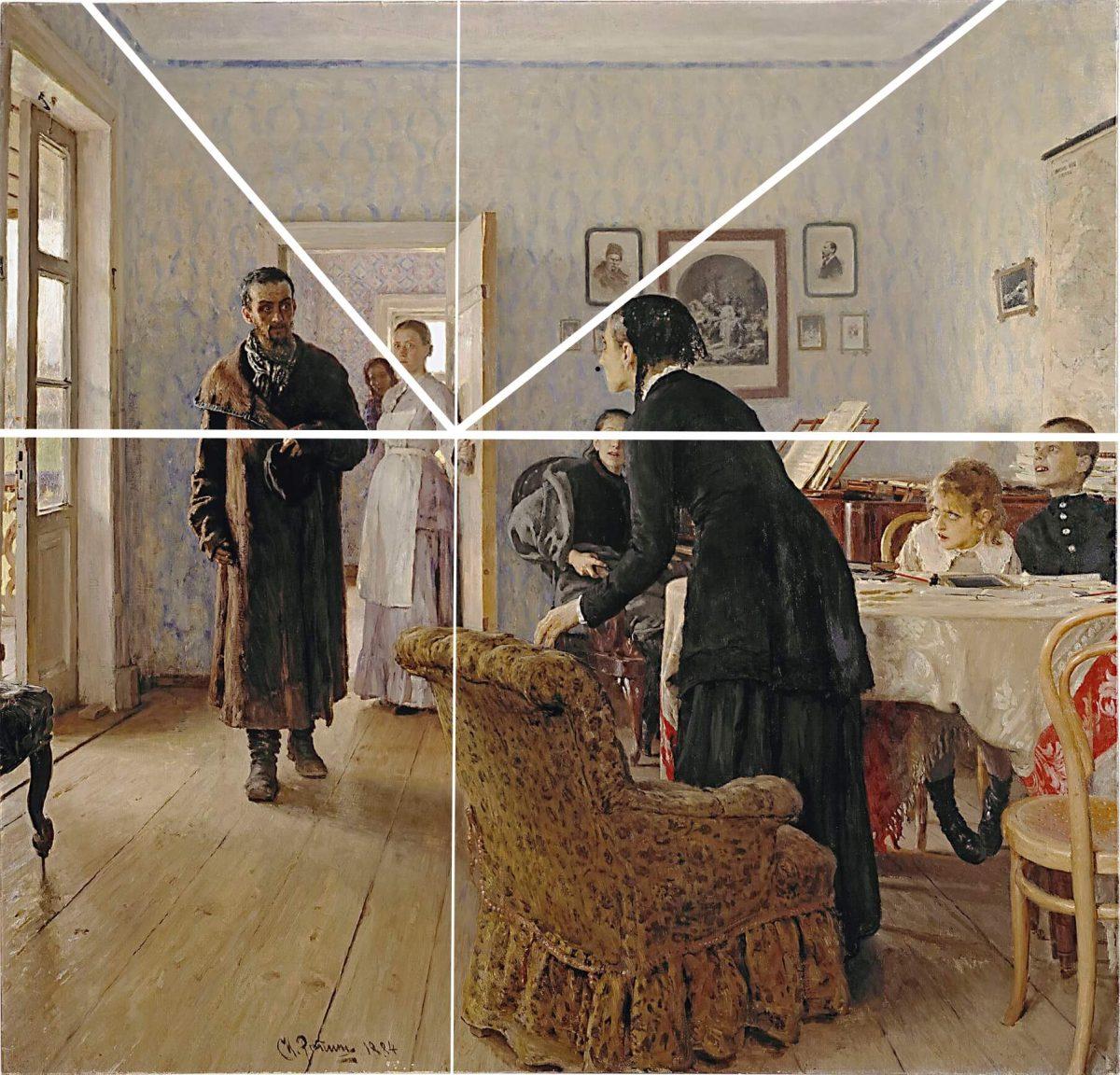

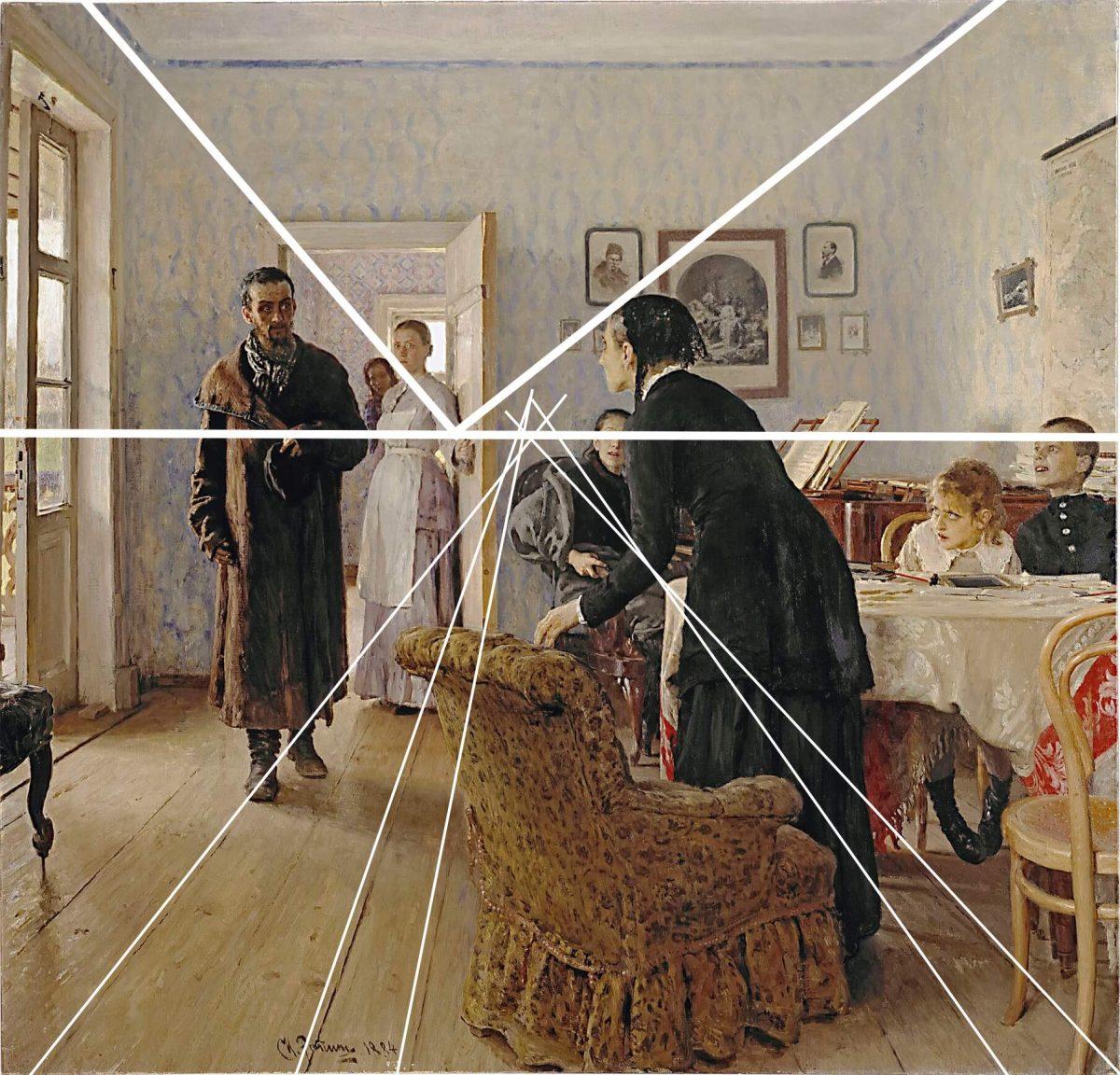

Ilya Repin. Didn't wait.

At first glance, the artist built the space according to the classical scheme. Only the vertical is shifted to the left. And if you remember, artists after the time of Leonardo tried to avoid excessive centering. In this case, it is easier to "place" the heroes along the right wall.

Also note that the heads of the two main characters, the son and the mother, end up in perspective angles. They are formed by perspective lines running along the ceiling lines to the vanishing point. This emphasizes the special relationship and even, one might say, the relationship of the characters.

And also see how cleverly Ilya Repin solves the problem of perspective distortions at the bottom of the picture. On the right, he places rounded objects. Thus, there is no need to invent anything with the corners, as Watteau had to do with his box.

And Repin makes another interesting step. If we draw perspective lines along the floorboards, we get something weird!

They will not join at a single vanishing point!

The artist deliberately went for the use of observational perspective. Therefore, the space seems more interesting, not so schematic.

And now we move to the XNUMXth century. I think that you already guess that the masters of this century did not particularly stand on ceremony with space. We will be convinced of this by the example of the work of Matisse.

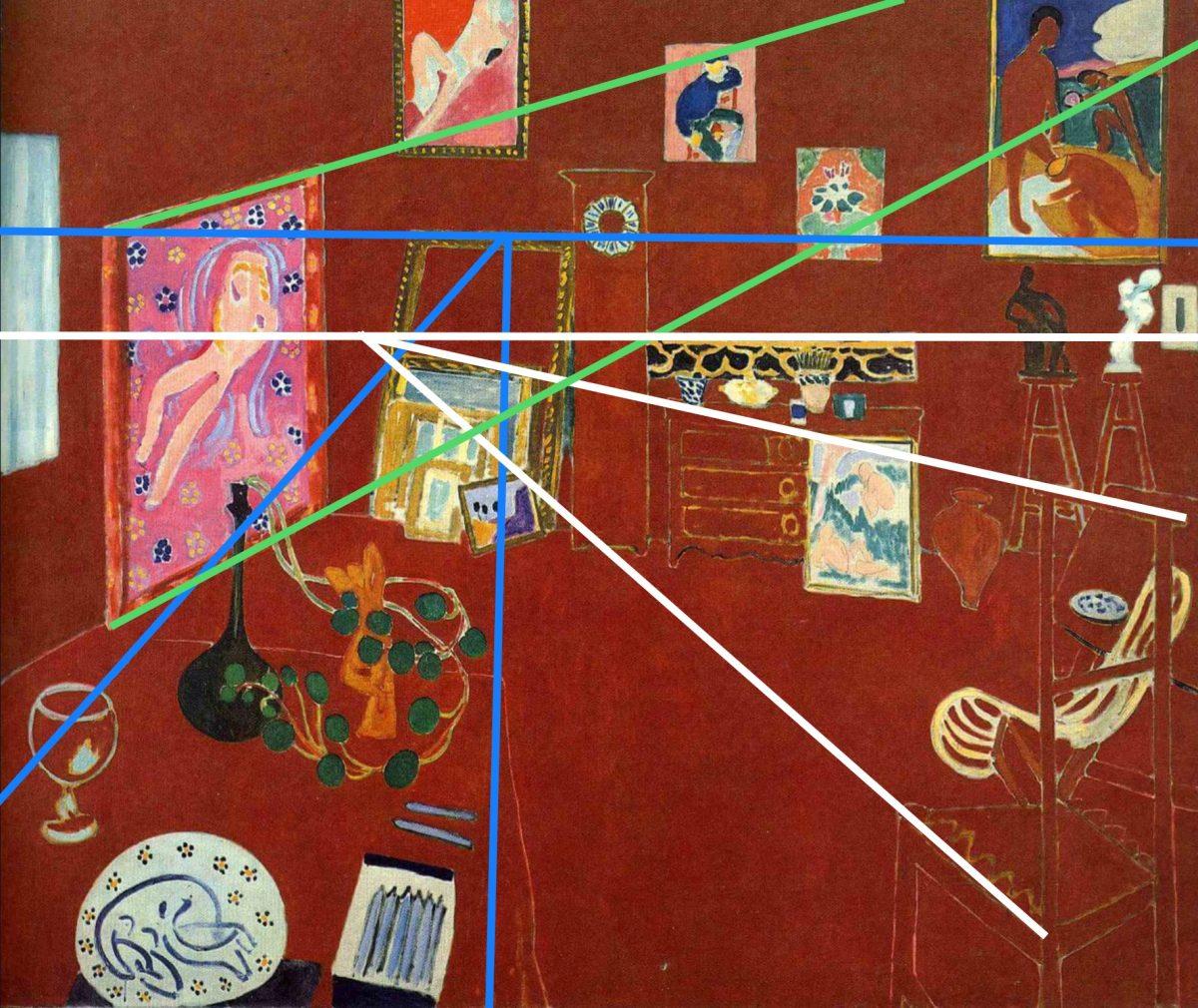

Henri Matisse. Red workshop.

Already at first glance it is clear that Henri Matisse depicted space in a special way. He clearly departed from the canons formed back in the Renaissance. Yes, both Watteau and Repin also made some inaccuracies. But Matisse clearly pursued some other goals.

It is immediately evident that Matisse shows some of the objects in direct perspective (table), and some in reverse (chair and chest of drawers).

But the features don't end there. Let's draw the perspective lines of the table, chair and picture on the left wall.

And then we immediately find THREE horizons. One of them is outside the picture. There are also THREE verticals!

Why does Matisse complicate things so much?

Please note that initially the chair looks somehow strange. As if we are looking at the upper crossbar of his back from the left. And for the rest of the part - on the right. Now look at the items on the table.

The dish lies as if we are looking at it from above. The pencils are slightly tilted back. But we see a vase and a glass from the side.

We can note the same oddities in the depiction of paintings. Those that are hanging are looking straight at us. Like the grandfather clock. But the paintings against the wall are depicted a little sideways, as if we are looking at them from the right corner of the room.

It seems that Matisse did not want us to survey the room from one place, from one angle. He seems to lead us around the room!

So we went to the table, bent over the dish and examined it. Walked around the chair. Then we went to the far wall and looked at the paintings that are hanging. Then they dropped their gaze to the left, at the works standing on the floor. Etc.

It turns out that Matisse did not break the linear perspective! He simply depicted the space from different angles, from different heights.

Agree, it's mesmerizing. As if the room comes to life, envelops us. And the red color here only enhances this effect. Color helps space draw us in...

.

It always happens that way. First, the rules are created. Then they start breaking them. Shy at first, then bolder. But this is not, of course, an end in itself. This helps to convey the worldview of his era. For Leonardo, this is the desire for balance and harmony. And for Matisse - movement and a bright world.

About the secrets of building space - in the course "Diary of an Art Critic".

***

Special thanks for help in writing the article to Sergey Cherepakhin. It was his ability to deal with the nuances of perspective constructions in painting that inspired me to create this text. He became his co-author.

If you are interested in the topic of linear perspective, write to Sergey (cherepahin.kd@gmail.com). He will be happy to share his materials on this topic (including the paintings that are mentioned in this article).

***

If my style of presentation is close to you and you are interested in studying painting, I can send you a free cycle of lessons by mail. To do this, fill out a simple form at this link.

Comments other readers see below. They are often a good addition to an article. You can also share your opinion about the painting and the artist, as well as ask the author a question.

Online Art Courses

English version

***

Links to reproductions:

Leave a Reply